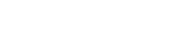

A snapshot taken a second before a powerful solar flare was unleashed from the Sun, as seen in unprecedented detail by Solar Orbiter. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

Scientists watched a solar flare grow from tiny magnetic sparks into a violent plasma-raining avalanche on the Sun.

Like snow avalanches that start with a small shift before rapidly growing, new observations show that solar flares begin with weak magnetic disturbances that intensify quickly. Scientists using the ESA-led Solar Orbiter spacecraft found that these early disruptions can escalate into powerful eruptions. As the process unfolds, glowing blobs of superheated plasma appear to rain through the Sun’s atmosphere and continue falling even after the flare itself begins to fade.

This discovery comes from one of the most detailed observations ever made of a large solar flare. The event was recorded during Solar Orbiter’s close approach to the Sun on September 30, 2024, and is described in a paper published on January 21 in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

An artist’s concept shows Solar Orbiter near the Sun. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Conceptual Image Lab

What Causes Solar Flares

Solar flares are massive explosions that release enormous amounts of energy from the Sun. They occur when energy stored in twisted and tangled magnetic fields is suddenly unleashed through a process known as reconnection. During this process, magnetic field lines pointing in opposite directions break apart and reconnect within minutes.

When the field lines reconnect, they can rapidly heat surrounding plasma to millions of degrees and accelerate high-energy particles away from the reconnection site. This sudden release of energy can trigger a solar flare.

The strongest flares can set off a chain of events that reaches Earth, sometimes causing geomagnetic storms and radio blackouts. This is why understanding how solar flares begin and develop is so important.

Solar Orbiter’s most detailed view yet of a large solar flare, with filaments, raining plasma blobs, magnetic reconnection events and X-ray emission labeled. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

A Longstanding Mystery Comes Into Focus

Until now, scientists did not fully understand how such an immense amount of energy could be released so quickly. The detailed sequence of events had remained unclear.

That picture has now changed thanks to an unprecedented set of observations from four Solar Orbiter instruments working together. Their combined data provide the most complete view of a solar flare ever assembled.

Solar Orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) captured high-resolution images of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona, focusing on structures just a few hundred kilometres across and recording changes every two seconds. At the same time, three other instruments, SPICE, STIX, and PHI, examined different depths and temperature ranges, from the corona down to the Sun’s visible surface, or photosphere. Together, these instruments allowed scientists to watch the buildup to the flare over roughly 40 minutes.

“We were really very lucky to witness the precursor events of this large flare in such beautiful detail,” says Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany, and lead author of the paper. “Such detailed high-cadence observations of a flare are not possible all the time because of the limited observational windows and because data like these take up so much memory space on the spacecraft’s onboard computer. We really were in the right place at the right time to catch the fine details of this flare.”

Solar Orbiter’s high-resolution images reveal the fine-grained detail of the ‘magnetic avalanche’ process that led up to the major solar flare of September 30, 2024. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

Magnetic Avalanche in Action

When EUI began observing the region at 23:06 Universal Time (UT), about 40 minutes before the flare reached its peak, scientists saw a dark arch-like filament made of twisted magnetic fields and plasma. This structure was connected to a cross-shaped pattern of magnetic field lines that slowly grew brighter.

Closer inspection revealed that new magnetic strands appeared in nearly every image frame, about every two seconds or less. Each strand remained magnetically contained and gradually twisted, resembling coiled ropes.

As more strands formed, the region became unstable. Like a snow avalanche gathering speed, the twisted magnetic structures began breaking and reconnecting. This triggered a spreading cascade of further disruptions, each one releasing more energy. The process appeared in the images as sudden and increasingly intense bursts of brightness.

At 23:29 UT, a particularly strong brightening was observed. Soon after, the dark filament detached on one side, launched into space, and violently unrolled at high speed. Bright flashes of reconnection appeared along the filament in striking detail as the main flare erupted around 23:47 UT.

“These minutes before the flare are extremely important, and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began,” says Pradeep. “We were surprised by how the large flare is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that spread rapidly in space and time.”

Solar Orbiter saw that, in the lead-up to a solar flare, twisted magnetic fields break and reconnect, creating an outflow of energy that subsequently rains down through the Sun’s atmosphere in ribbon-like streams. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

A Solar Flare as a Chain Reaction

Scientists had previously proposed avalanche models to explain the collective behavior of hundreds of thousands of flares on the Sun and other stars. What remained uncertain was whether a single large flare could also follow this pattern.

These observations show that it can. Rather than forming as one unified explosion, a major flare can emerge from a cascade of interacting reconnection events that build on one another to release vast amounts of energy.

The evolution of X-ray emission during the M7.7 class solar flare recorded by Solar Orbiter in high resolution on 30 September 2024. The coloured contours outline the X-ray source regions detected by the mission’s X-ray Spectrometer/Telescope (STIX) instrument at the measured levels indicated in the key, superposed on top of the images recorded by the mission’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI). Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI & STIX Teams

Raining Plasma Blobs

For the first time, researchers were able to examine how this rapid sequence of reconnection events deposits energy into the outermost layers of the Sun’s atmosphere in extremely high resolution. This was made possible by simultaneous measurements from Solar Orbiter’s SPICE and STIX instruments.

High-energy X-ray emission was especially important because it reveals where accelerated particles release their energy. Since these particles can escape into space and pose radiation risks to satellites, astronauts, and Earth-based technology, understanding this process is essential for space weather forecasting.

During the September 30 flare, emissions ranging from ultraviolet to X-rays were already slowly increasing when SPICE and STIX began observing the region. As the flare intensified, X-ray emission rose dramatically as reconnection events multiplied. Particles were accelerated to speeds of 40 to 50 percent of the speed of light, or about 431 to 540 million km/h. The observations also showed that energy was transferred directly from the magnetic field to the surrounding plasma during these events.

“We saw ribbon-like features moving extremely quickly down through the Sun’s atmosphere, even before the main episode of the flare,” says Pradeep. “These streams of ‘raining plasma blobs’ are signatures of energy deposition, which get stronger and stronger as the flare progresses. Even after the flare subsides, the rain continues for some time. It’s the first time we see this at this level of spatial and temporal detail in the solar corona.”

Solar Orbiter’s Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) instrument observed the wider-field imprint of the flare on the Sun’s visible surface (photosphere) in impressive detail, completing the three-dimensional picture of the flare. Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/PHI Team

Cooling and Aftereffects

After the most intense phase of the flare, EUI images showed the original cross-shape magnetic structure relaxing. At the same time, STIX and SPICE observed plasma cooling and a decline in particle emissions toward normal levels. PHI detected the imprint of the flare on the Sun’s visible surface, completing a three-dimensional view of the event.

“We didn’t expect that the avalanche process could lead to such high-energy particles,” says Pradeep. “We still have a lot to explore in this process, but that would need even higher resolution X-ray imagery from future missions to really disentangle.”

Why This Discovery Matters

“This is one of the most exciting results from Solar Orbiter so far,” says Miho Janvier, ESA’s Solar Orbiter co-Project Scientist. “Solar Orbiter’s observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasise the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work. An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars.”

“These exciting observations, captured in incredible detail and almost moment by moment, allowed us to see how a sequence of small events cascaded into giant bursts of energy,” says David Pontin of the University of Newcastle, Australia, who co-authored the paper.

He adds: “By comparing the EUI observations with magnetic-field observations, we were able to disentangle the chain of events that led to the flare. What we observed challenges existing theories for flare energy release and, together with further observations, will allow us to refine those theories to improve our understanding.”

Reference: “A magnetic avalanche as the central engine powering a solar flare” by L. P. Chitta, D. I. Pontin, E. R. Priest, D. Berghmans, E. Kraaikamp, L. Rodriguez, C. Verbeeck, A. N. Zhukov, S. Krucker, R. Aznar Cuadrado, D. Calchetti, J. Hirzberger, H. Peter, U. Schühle, S. K. Solanki, L. Teriaca, A. S. Giunta, F. Auchère, L. Harra and D. Müller, 21 January 2026, Astronomy & Astrophysics.

DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202557253

Solar Orbiter is an international mission developed by ESA and NASA and operated by ESA. The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) is led by the Royal Observatory of Belgium (ROB). The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI) is led by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), Germany. The Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) is a European-led instrument led by the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS) in Paris, France. The STIX X-ray Spectrometer/Telescope is led by FHNW, Windisch, Switzerland.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.

https://scitechdaily.com/solar-orbiter-reveals-how-solar-flares-really-begin/